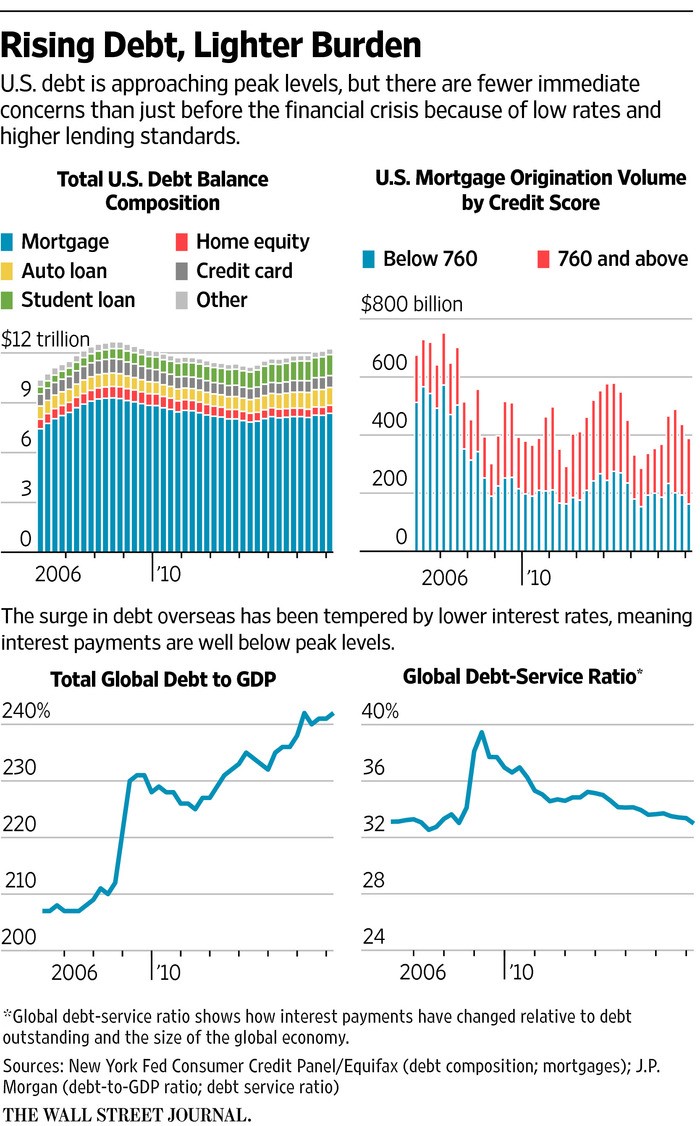

If current trends persist through the end of the year, U.S. households will owe as much as they did at the peak of borrowing in 2008.

Global debt has already topped 2008 levels and keeps rising. That’s pretty astonishing so soon after debt-driven crises in the U.S. and Europe and endless worries about too much borrowing in Japan, China and emerging markets.

But for all the hand-wringing, a near-term debt crisis is unlikely. Lower interest rates mean debt payments are far lower than they were before the crisis. In the U.S., household debt compared with the overall economy is way down. And overseas, loans can easily be rolled over.

Yet even with low rates, the cycle of borrowing and rolling over loans has a cost. People, governments and businesses spend now instead of later, likely reducing future growth. The cycle also allows borrowing to go on for years, which can be good—allowing reform to take hold—or not, allowing bad policies go on almost indefinitely.

U.S. households owed $12.25 trillion at the end of the first quarter, up 1.1% from the end of 2015, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, released Tuesday. If the first quarter repeats itself through the end of the year, U.S. household debt will approach its peak of $12.68 trillion, which it hit in the third quarter of 2008.

Many people remember that quarter because it’s when the global financial system went off a cliff.

This time is different because short-term interest rates have been stuck near zero since then. For U.S. consumers, that means household debt-service payments as a percent of disposable personal income are at their lowest level since at least 1980, despite a much higher debt load. In addition, more loans are going to higher-quality borrowers.

The combination of better-quality borrowers, plentiful jobs and low rates means U.S. default rates are at historic lows.

Low rates have had an even more dramatic impact overseas, where economies are weaker or less stable. Global debt—including households, businesses and governments—has risen from 221% of GDP at the end of 2008 to 242% at the end of the first quarter. But the cost of interest payments, as a share of GDP, has fallen to 7% from a peak of 11%, according to J.P. Morgan.

Japan is the prime example of how low interest rates can change the rules of the game. At 400% of GDP, Japan’s debt level is by far the highest in the world. One of the great mysteries of finance is why investors lend the government money for negligible or negative yields when it seems impossible for Japan to pay off its debt.

But Japan’s interest-cost-to-GDP ratio is just 2%, among the lowest in the world, according to J.P. Morgan. At that level and with ample domestic savings, that game could go on forever.

Japan’s example eases some of the short-term worries about China, where borrowing to juice the economy has become national policy. Debt to GDP in China has risen from just over 140% before the financial crisis to 243% currently. But China’s interest cost to GDP is 12%. That’s among the highest in the world, and higher than the U.S. precrisis, but the ratio hasn’t risen in two years, even as borrowing increased.

More important, China has plenty of room to cut interest rates. And lenders are also rolling over loans and extending maturities. Debt can’t rise forever, but if there’s no big shock in China, there’s little reason the debt game can’t keep going for the foreseeable future.

“In a world where rolling over debt is not difficult, the sustainability of debt should be driven by interest costs,” said J.P. Morgan analyst Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou.

The risk is that rising inflation could prompt central banks to push up interest rates. But inflation, too, eases the debt burden by allowing borrowers to pay back loans with cheaper money. That’s the best-case scenario for the Japanese government to pay down its debt.

The losers in all of these scenarios are savers and lenders, who hardly get paid at all for providing capital—and then risk losing money in real terms.

There’s also stress among some borrowers. Student loans in the U.S. now account for 10% of household debt, double the level in 2008, and 11% of that is in default or close to it. In emerging markets, falling commodity prices and weak currencies make it difficult for some countries to pay off debt denominated in dollars.

The ability to pile on debt with few consequences inevitably leads to complacency. While the quality of debt in the U.S. is by and large good, that isn’t the case in China. Estimates of bad loans on bank balance sheets range up to 19%, compared with the official estimate of nonperforming loans of 1.6%. Standard Chartered estimates Chinese debt will top 300% of GDP by 2020.

Any shock, such as renewed capital flight at home or a big recession abroad, could tip China, and even Japan, into crisis. The circumstances that allow big accumulations of debt can go on a very long time, but they never last forever. That’s the risk the global economy will face, at some point.